When you start to see signs of cognitive decline

Don't wait to act when you suspect dementia.

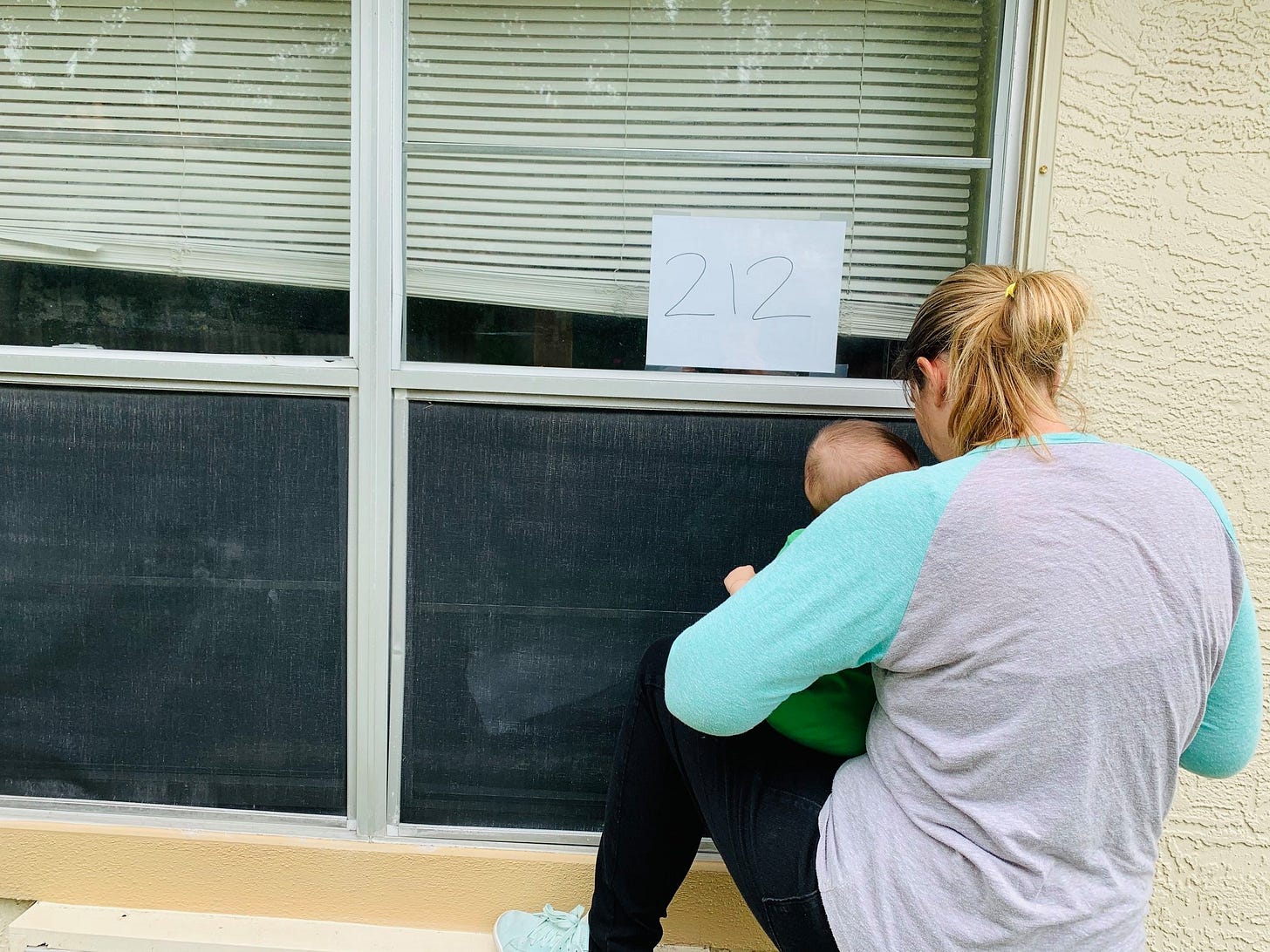

My dad was in and out of rehabs and nursing homes in 2020 and 2021, and because of pandemic restrictions, I wasn’t able to stop by and check on him. Instead, I called multiple times a day.

One time, when I asked to speak to my dad, the nurse who answered the phone just sighed heavily.

“I have to let you know of something your father said yesterday,” she said. “Apparently he and his roommate have been butting heads. I know he’s former military, your father, and that there’s a way about former military, but he can’t be threatening people.”

“I’m sorry, what?” I asked. I choked back a laugh. My father had threatened someone? My father, who served in the Air Force in a paperwork, not piloting, capacity, was identifying as “former military”?

“Someone overheard him saying that if his roommate didn’t shut up, he was going to rip out his throat.”

I laughed. I just couldn’t help it. My father couldn’t walk! He couldn’t wipe his own ass—how was he going kick someone’s ass? It was absurd. Also, my father was frequently thought of as the gentlest, kindest person, the best dad. And here he was, threatening some 90-year-old.

The nursing home switched his room, and his new roommate was much quieter and didn’t elicit the same rage from my father. But I never met either one. I was never able to assess whether the guy really was a loud asshole as my father claimed, or whether my dad was being ridiculous and mean, as the staff asserted.

One of the signs of a urinary tract infection in older adults is the appearance of dementia-like symptoms. A UTI can cause confusion, disorientation, and agitation. In his old age, my father was prone to UTIs, and he always became not only agitated but also verbally abusive and delusional.

Once, in the hospital, he acquired a UTI that went undetected for some time. He had a dream he was a Union soldier trapped in a Confederate prisoner camp. He ripped out his IVs and flopped out of the bed, trying to escape. (I joked that I was relieved he was on the right side of history, even when he was out of his mind.)

More than once, he called me, livid. “Get me the fuck out of here,” he would say. He would insist he could walk, he could use the bathroom, he could take care of himself.

“Dad,” I would say, carefully. “I’ll talk to the nurses. But they tell me—”

He cut me off. “They tell you what they want to tell you because they want to keep me here! They want the money! That’s all I am to these people! A paycheck! Get me out of here, goddammit!”

Sometimes I tried to reason with him. “Dad, as soon as you’re able to walk, to transfer between the wheelchair and the toilet, you can come home.” He could do that, he insisted; the nurses were lying.

Unfortunately, if your parent is in the midst of true cognitive decline, whether it’s a result of a medication, an infection, or a disease, it may be hard for them to fully comprehend. Kernisan and Scott explain in their excellent guide, “When Your Aging Parent Needs Help”:

“When cognitive issues are present, brain functions that support logic, judgment, and rationality are affected. No matter how hard you try, no matter how patient your explanations, your parent may become upset, hold a decision against you, or behave in other uncharacteristic ways.”

Once, I yelled back at him. “They are not trying to get your money! If you weren’t in that bed, someone else would be! I assure you, you are no picnic!”

He hung up on me.

I gently suggested to the nurses that perhaps he was suffering from a UTI, perhaps that was leading to his uncharacteristic behavior with his (even more) elderly roommate. Once he got antibiotics, he returned to his normal disposition with no memory of having yelled at me.

Other than these experiences with temporary cognitive changes brought on by infections, neither of my parents had dementia.

But experts estimate that more than 7 million Americans had dementia in 2020, and as baby boomers age, that number is expected to rise to more than 9 million by 2040. Not all types of dementia are the same, and not all cognitive changes you observe in your parent indicate dementia.

Does your parent need a cognitive evaluation?

If you’re starting to notice cognitive changes in your parent, it’s important to figure out the cause. Perhaps, like with my dad and my mom’s best friend, the changes are the result of an infection or the side effect of a medication. Once the underlying cause is addressed, they might go back to their normal level of cognition. Or maybe the cognitive changes are the result of the normal aging process and aren’t interfering with their daily lives and can be simply watched without being treated. Or, it could be that your parent is experiencing the early signs of a bigger problem: Alzheimer’s, Lewy body dementia, or other illnesses.

Knowing what’s causing your parent’s cognitive decline is essential, as it will allow your parent’s doctor to direct their treatment, and it will give your parent a say in that treatment before they potentially lose the ability to weigh in. Waiting to address this until it becomes a big problem may reduce your parent’s options. There are medications, for example, that can help in the early stages of dementia but that are not prescribed once it’s significantly progressed.

Also, there are factors that are correlated with an increased likelihood of dementia, and if you mistake these for dementia symptoms and ignore them out of fear, you may be inadvertently allowing them to continue and worsen. This includes problems with hearing, vision, social isolation, and head injuries from falls.

It’s natural to be afraid of finding out your parent has dementia, but if you think they probably should be evaluated, I suggest you trust your gut and help them talk to their doctor about it. Like most things with aging parents, waiting until it’s a bigger problem means taking agency away from your parent and putting more of the burden on you.

If they find out they have Alzheimer’s or another form of dementia, there are legal steps they may want to take while they still can. There are things they may want to say or do before they lose the ability to do so. Getting a diagnosis of dementia is hard, but delaying getting one makes things so much harder.

Observing Your Parent for Signs of Cognitive Decline

When you think about your parent’s mental health and cognitive abilities, ask yourself the following:

Is your parent still seeing friends and family often? Do they seem lonely?

Are they still doing hobbies or activities they enjoy?

Do they seem to get lost while driving or walking, even to places they’ve been before?

Are they having trouble coming up with the right words in conversation, or more trouble pronouncing and enunciating?

Do they follow through on things they said they would do?

Do they have trouble following a movie or a conversation? If they were a reader, are they reading less?

Is their eye contact consistent, or do you notice an increase in staring off into space or a glassy-eyed expression?

Are they forgetful in a weird way? (Like asking what the toaster does or putting the milk in the cabinet instead of the fridge.)

Do they repeat conversations, stories, or questions often? Has this increased recently?

Have you seen your parent misjudge distance or vision? For example, missing the table when they go to put down a cup?

Have they been keeping up with finances? Spending money in unusual ways?

Does their personality seem to have changed? Are they grouchy when they were once easygoing? Sarcastic and mean when they were once sweet? Or placid and easy when they were once feisty and opinionated?

Are they falling more frequently?

Things you can do:

RESEARCH: Which providers in your area do cognitive evaluations? Which are covered by your parent’s insurance? Which are recommended by your parent’s doctor? What is the process for getting an evaluation? Is there a waitlist?

CONFER: Talk to your siblings or other relatives or friends who know your parent well. Are they seeing the same things? Do they also have concerns? If your parent is unlikely to heed your advice, perhaps enlisting another person in their life to encourage them to seek help would be beneficial.

DISCUSS: Talk to your parent about your concerns, if you think they’ll be open to it. If you suspect you will encounter resistance or defensiveness, or if you try once and encounter these things, consider the “what if” approach:

“Dad, a lot of people your age start to show signs of cognitive decline. What would you like me to do if I start to notice that in the future?”

DISCUSS: Talk to your parent’s doctor or to your geriatric care manager, if you have one. It can take months (or years) of waiting to get an appointment for an evaluation, so start this process far before you think it’s absolutely necessary.

TRACK: Keep track of physical and cognitive changes you see in your parent, noting when they began, so you can have a record of the changes when you discuss them. I created this free tracking template that you can use and add to as you observe changes in your parent’s physical and mental capacity.

I went through all this with my dad, who died of dementia-related issues. But my question is: what do people do when their parent with dementia refuses to go into a nursing home? My dad was always stubborn, but 1000% more when he had dementia, and it was very harmful to my mom, his primary caregiver. But we certainly had an extremely difficult time getting him

Into care.

There are some great pointers here, Lauren. Are you ok if I add this to the Dementia Anthology in Carer Mentor? Here in the UK, I've heard from a few carers who've sought a diagnosis but it's taken a long time despite experiencing several points you raise here.

For us, Dad's diagnosis of vascular dementia was quick because of the abrupt changes and issues.