Why you should start your parent's obit (while they're still here)

Getting started now will bring you closer to your parent and make your life easier when they're gone

My friend Kristen Hare is really good at asking questions about dead people.

She is a journalist, educator, and author who has both written obituaries for the Tampa Bay Times and other outlets and studied obituary writing. I asked her what advice she’d give someone just starting to think about their parent’s obituary, and she was emphatic: “Start right now.” No matter how your parent is doing, health-wise, you can start right now.

“You can do that with your well parent—just say, ‘hey, here’s what we’re doing: once a week, I’m going to send you an email with three questions, and I need you to answer them for me.’ Even better if you can do it in person, even better if you can record their voice, because that’s not something you get back once they’re gone,” she says.

In 2020, Kristen’s favorite uncle was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, and they knew his death was imminent. She made the trip to St. Louis to say goodbye and to ask him as many questions as she could, to help him record an oral history of his life.

When Kristen sat down with her uncle, she knew she wanted to learn about his life, but more than that, she wanted to give him the gift of sharing himself with his family even after he was gone.

If you decide to do this, you don’t have to be so formal as to call it “recording an oral history.” You can simply tell your parent you are planning to ask them some questions about their life and that you want to record it (on your phone’s video or voice memo app).

“Sit down and ask as many questions as you can—the Smithsonian has a guide for oral histories—there are things you wouldn’t even think to ask. Like what did your street look like when you were growing up? What did you eat for lunch in elementary school? And the stories those kinds of questions elicit, they were just so rich and helped me understand even more who this person I loved so much was and what shaped him.”

There are so many questions I wish I’d asked my own parents. About my own life but also about theirs. What did you want to be when you grew up? What are you most proud of? Why did you really move to Florida? Was it hard not having family around? Was it also hard for you, being a mom without a mom?

After your parent is gone, when you are in the fog of grief, it will feel impossible to write their obituary. If you have asked them some questions, maybe even started writing, prior to their death, it will be easier. To do that, Kristen says, you may have to be blunt about it.

“Say: ‘I don’t want you to have a boring obituary. I want to write about the stuff that you love. I want you to feel that you’re reflected in this. Can you help me do this? Or can we talk about what you might be comfortable with? Because this might not happen for 20 years, but I want to be prepared when it does.”

ACTION STEPS

I bet if you think about it, you have lots of questions you don’t ever ask because it feels too personal or to awkward. The real question for you, though, is whether overcoming your feeling of awkwardness is worth the answers you’ll get.

Check out the Smithsonian Center for Folklife & Cultural Heritage guide for oral histories (but do not let this intimidate you!)

Brainstorm a list of things you’re curious about, perhaps including the following: your parent’s childhood, your grandparents, family traditions, your parent’s work life, your parent’s significant relationships, your parent’s experience becoming a parent, your parent’s education, hobbies, trade, or passions. Create a list also of things you want to know about your own life, that only your parent can answer.

If sitting down to record an oral history or do an interview feels just too daunting, consider glancing at the list you have in a Notes app on your phone. Maybe ask one question each visit. You don’t have to turn every interaction into a weird little interview, but you only have so much time with people, and if there are things you want to know, you have to ask.

Another alternative is providing a journal or gifting your parent a subscription to a storytelling app. If you search “journal for elderly parent,” you’ll see lots of modern options.

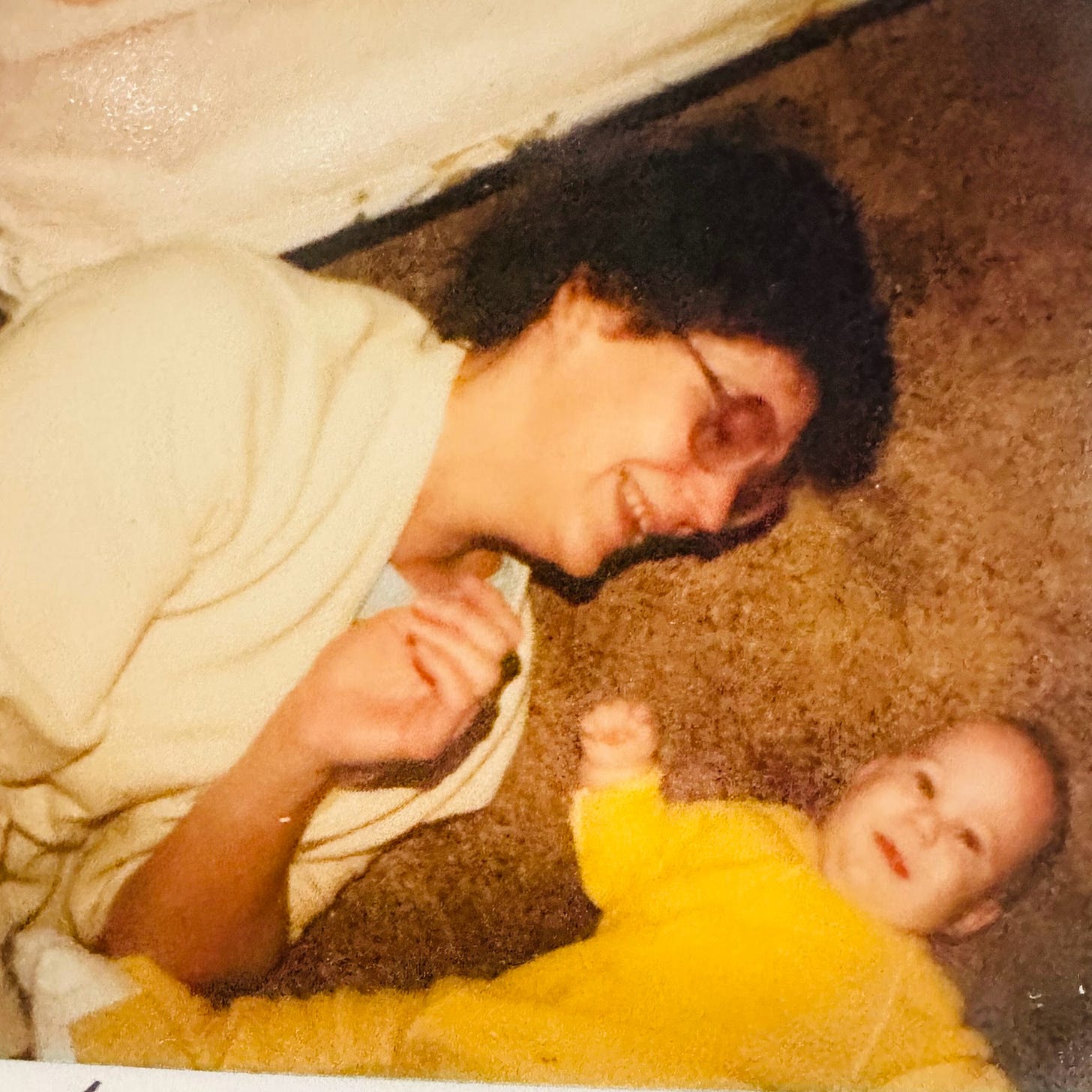

If it feels weird to just ask questions, you can also ask about photographs or objects. I have a jewelry box full of my mom’s pendants, rings, brooches, and bracelets, and I wish I had thought to ask her who gave her each piece, where she got it, and why she kept it.

Even if you are not going to do an oral history, consider how you can record your parent’s voice. Are you casually making a video of your kid and your parent is in the room? Are you saving voicemails and emailing them to yourself or saving them to the cloud? You can’t go back and record this later, so be sure to save copies.

Another idea might be to ask your parents to describe all of the old family pictures..."who is that?" and "when was that?"

During COVID lockdown, my cousins and I created a digital family album, sharing pictures with captions so that the kids would know who was who, etc.

Great tips and ideas, Lauren. You may want to connect with @Sarah Coomber who organised sessions on writing our own obituary, as a planning exercise.